It’s just a coincidence that this is the second week in a row that I’ve been looking at manuscripts. And that makes for quite a treat, even if all of the pages and words become overwhelming after a time. It’s certainly an unbelievable privilege to be able to travel to lovely places, and especially to sit in the ancient Ambrosian Library in Milan and turn the pages of an immense, heavy, unspeakably beautifully decorated volume of saints’ lives. But I couldn’t take any photos of that, and I’m more academically excited by the manuscript that was my primary reason for going to Italy, which is held in the bishop’s archives in Novara, a small city about an hour west of Milan by train. So that’s what the rest of this blog is about: Novara, Archivio Storicio Diocesiano, MS P. 2 (s. xii, Novara?).

There are a number of unique things about the way the story of Christopher is told in this volume. Probably as a result, it’s catalogued in quite a confusing way, which is why I really wanted to see it. I can confirm – against all of the lists I’ve seen – that it’s actually part of the BHL 1771 line of the text (which comes from southern Germany). But this interests pretty much no-one apart from me, and is merely a technical distinction. That sort of classification is not why I look at manuscripts.

What’s really interesting (I think) is how the story is retold here. The single biggest difference is that the story of two very powerful women, which is at the heart of the usual Christopher narrative, is cut down quite heavily, and their importance minimised. I’ll probably blog about them separately at a later date; here, this is just an example of the revisions taking place. The (many) speeches and prayers are also consistently lengthened in this copy, often with increased orthodoxy compared with some of the oddities of the older and more common variant.

Once you’re looking at a unique text, one of the questions to ask is how long before this particular copy of the text the version was produced. Is it just random chance that this single copy has survived, or might this be the manuscript in which the story was first revised in this way? In other words, was the scribe just copying out something in front of him, of interest to me (because I haven’t seen it elsewhere), but not especially so to him (because he had to copy out Christopher’s story, and this was the version he had). Or was he a revising scribe, acting as author at the same time as copying – or at least in the company of an authorial figure?

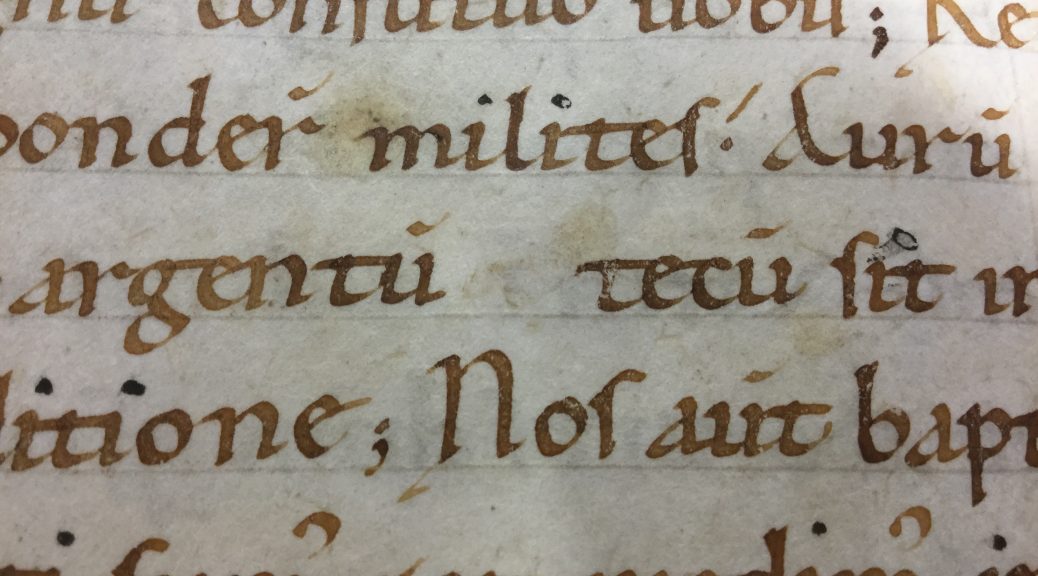

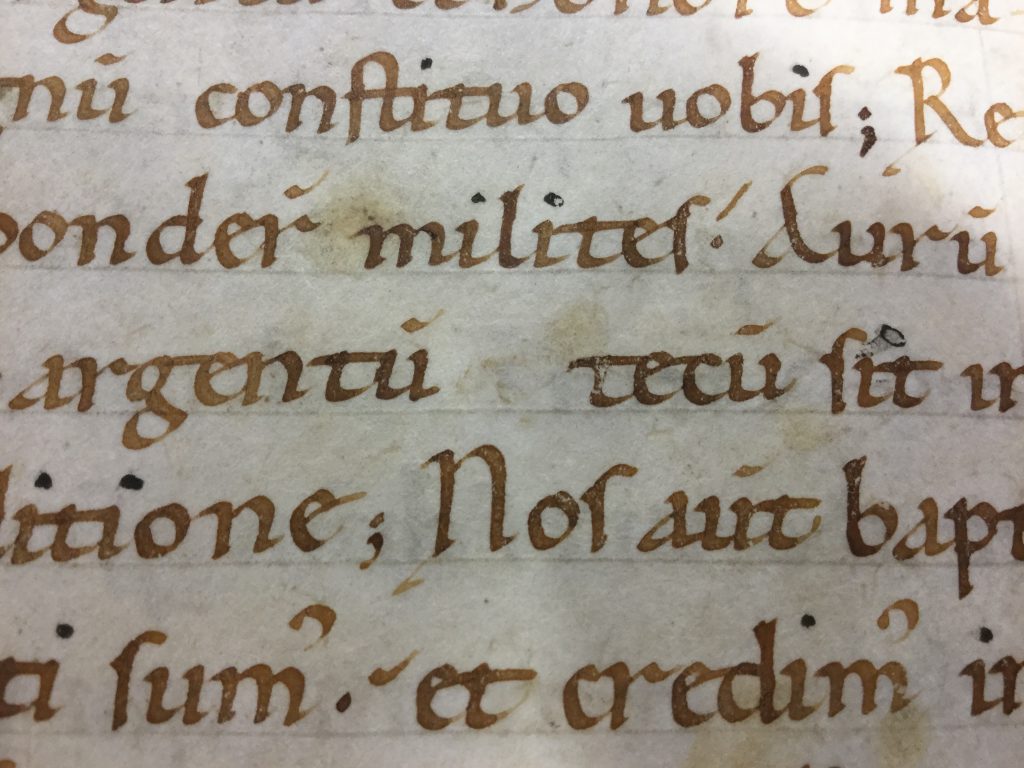

I need to do more work on this, and I’ve seen six manuscripts in the last two weeks, so I’ve got a lot of notes to sort out. But there are indications that this copy might be by the ‘author’ of this version. The most straightforward evidence is an erased letter t, shown in the picture here.

In this bit of text, some soldiers tell their king to get stuffed; they’ve had enough of doing what he says, because he’s a psycho, and they’re going to become Christians. He offers them gold and silver to change their minds (which is a bit Game of Thrones). In the standard telling, they say ‘screw your gold and silver’ (“aurum et argentum tuum sit in perditione”). In this version, they say “screw gold and silver”, missing out the tuum (your) in the Latin. But the scribe started to write the tuum, getting as far as the t, then realised his mistake – or changed his mind – and deleted it instead. His soldiers reject all worldly wealth, not just the money connected with the evil kind; a change in line with many of the other revisions that can be seen in this copy.

That’s not conclusive, but (along with the other stuff) suggests that, as he read and copied out this story, he was thinking about it, changing it, retelling it in a new way. This twelfth-century manuscript is a living piece of storytelling; an individual’s reaction to the story I’m engaging with each day I work on this project. That I disagree with his reading maybe only makes it more exciting to see what he’s done with it. It’s been a great couple of manuscript weeks, but being sat in the archives of the bishop’s palace on Wednesday and seeing that scratched out t was the best moment of them.